Following an interaction with "Rock Mada" on Twitter/X as a result of his tweet about DBS, The discussion led me to think that it might be interesting to share my professional journey in Minnesota.

I usually don't write about myself. The posts on the blog typically deal with my insights on sports or life in Minnesota and the USA. However, ultimately, the reason I came here and why I am still here is a fascinating professional endeavor that, in addition to being interesting, I believe is also important and worthy.

I Hope you enjoy it.

Background – What is DBS

Our startup, Surgical Information Sciences, or SIS for short, is a medical device company developing software products in the field of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS).

Deep Brain Stimulation is an amazing medical treatment that has been around for about 20 years. It involves a surgery where an electrical electrode is implanted into the patient's brain. The electrical stimulation of the area in the brain where the electrode is placed significantly improves the condition of patients. Medicine uses DBS to treat various diseases, such as Parkinson's, dystonia, or epilepsy. For each disease, there is a different target area in the brain, sometimes only a few millimeters in size, where the electrode needs to be placed.

SIS focuses on brain areas related to DBS treatments for Parkinson's patients. Here's a video that excellently demonstrates the effect of successful DBS surgeries for Parkinson's patients.

The Problem

One of the main issues in DBS surgeries, and one of the reasons they are not used more, is the difficulty in precisely placing the electrode at the target. Studies have shown that if the electrode is placed exactly at the target, the benefit of electrical stimulation to the patient is high. When the placement is not accurate, even if it's a deviation of just one millimeter from the target, the benefit to the patient decreases, and in more severe cases, side effects may occur. The difficulty in placing the electrode precisely at the point arises from several reasons:

Size of the targets: Only a few millimeters.

Clarity in identifying target areas: The ability to see where the surgeon needs to reach with the electrode in pre-surgery brain scans – some DBS targets for Parkinson's patients cannot be seen at all in MRI scans of the brain.

Accuracy of navigation systems: The surgeon's ability to reach the target with the electrode with maximum precision.

Surgical accuracy: Even if the target is clear, it's physically possible to miss the electrode placement.

Other factors: Patient movement (DBS surgeries are performed while the patient is awake) or brain shift when drilling (apologies for the graphic description).

The DBS market is large, and the world's major medical device companies are intensely involved in the field. SIS attempts to solve the second problem on the list – the assumption is that if the medical team can clearly see the targets, it will be easier to plan navigation to the target and navigate effectively. Therefore, SIS produces accurate mapping and clear visualization of DBS targets for Parkinson's. The hope is that as a result, the success rates of surgeries will increase, the benefit to patients will grow, and the use of DBS technology will expand.

The Solution

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) devices are magnet-based imaging machines. Magnet strength is measured in Tesla units. In most hospitals worldwide, MRI machines have magnets with a strength of 1.5 or 3 Tesla (1.5T, 3T). At the University of Minnesota, where SIS was founded, there is a large research center with 7T MRI machines (seven Tesla).

In brain scans using 7 Tesla imaging devices, details can be seen, such as DBS targets for Parkinson's surgeries, that are not visible in 1.5 and 3 Tesla devices (also known as clinical MRI machines). Given brain images of the same patient at 7 Tesla and 1.5 Tesla, it is possible to train the computer to "find" the targets, which are clearly visible in the 7T image, also in the clinical image.

Stage One – Establishment

When I arrived in Minnesota, I knew almost nothing about what I’ve described so far. I brought with me only my professional experience, academic education, and an endless willingness to learn new things. My philosophy has always been that there’s nothing in my profession that I cannot do – there are only things I’ve already done and things I have yet to learn. In a small startup, there’s no room for saying, “That’s not my field, so I can’t do it.” You do whatever is needed, and if you don’t know how, you figure it out as you go.

I joined SIS with the goal of transforming an idea – along with some initial lines of code written at the University of Minnesota by the company’s founders – into a fully developed, software-based medical device. There was no roadmap, no instructions on what needed to be done. So, I took the initiative and started building from the ground up.

The first steps were about laying the foundation – setting up a functioning software company. This meant everything from creating email accounts for the team to selecting coding frameworks and project management tools. The decisions made at the beginning tend to stick with you the longest, which is why I put significant thought into choosing the right technologies and workflows. It was the start of a long and complex journey, but one that was exciting and full of potential.

The second step was to find someone to think things through with. I have enough experience to know that I don’t know everything, and in addition, the chances of making mistakes are lower when multiple people think together. Since I didn’t know anyone in Minnesota, I brought in an Israeli friend. It worked great.

After laying the foundation, another member joined the programming team. This was a significant milestone because it was probably the best hire of my life. I don’t know if it was luck, intuition, or a bit of both, but I met – and managed to recruit – a top graduate from one of the best universities in the U.S., a software prodigy, a true genius. I found someone who would become a real companion on this journey, the person I would spend most of my time with in the U.S., and a partner from whom I would learn so much. I will never understand what he was doing in Minnesota instead of making millions in Silicon Valley… but you don’t complain when you win the lottery.

Since the company had been operating long before I arrived in Minnesota, the initial power dynamics were such that the academic researchers led the development, while the software engineers were primarily responsible for implementing the code developed by the researchers. SIS was born as an academic research company. The company’s founders, all university faculty members, viewed things from a research-oriented perspective. Naturally, coming from a software industry background, I saw things differently. This conflict challenged all of us more than once, but it also brought diversity and intrigue.

Stage Two – Product Development

The first two years were dedicated to integrating all the components into a complete software product and establishing the platform in the cloud. Gradually, the concept evolved into a product that processes MRI scans (taken before surgery) and CT scans (taken after surgery, once the electrodes are already in the brain…), predicts the target areas before surgery, and visualizes what actually happened post-surgery – specifically, how accurately the electrode was placed relative to the planned target.

Similar to many startups, at this very stage, our company faced financial challenges. Suddenly, most of the neuroscientists and the Israeli friend who had come to Minnesota had to leave and move on, leaving only the American prodigy, myself, and an ocean of uncertainty. Fortunately, in early 2018, new management with a fresh vision entered the company.

Technically, despite everything that had been done in the first two years, it was clear to me that the product was still not what it needed to be. In my first meeting with the new CEO, I was asked what was needed in the development team and the company's R&D efforts. I responded that, given the company's situation at that time and in the foreseeable future, there was nothing that my American colleague and I couldn't handle. This was not a trivial statement. On one hand, for the first time, there were no neuroscientists on the team, and I had no idea how we would handle challenges outside our expertise. On the other hand, my vision – of software engineers leading research and development – had never felt more realistic.

Stage Three – Transformation

To better understand what is happening at SIS from now on, stay with me for a moment as I introduce two fundamental technical concepts in the world of image processing and artificial intelligence, particularly in medical imaging and 3D visualization – registration and segmentation.

Registration is a process in which two different elements, usually in a three-dimensional space, are adjusted so that they align as precisely as possible with each other. It’s like taking two Rubik’s cubes and fitting them into one another in perfect color alignment. In the examples below, you can see two registration processes of two different brain images in each case –

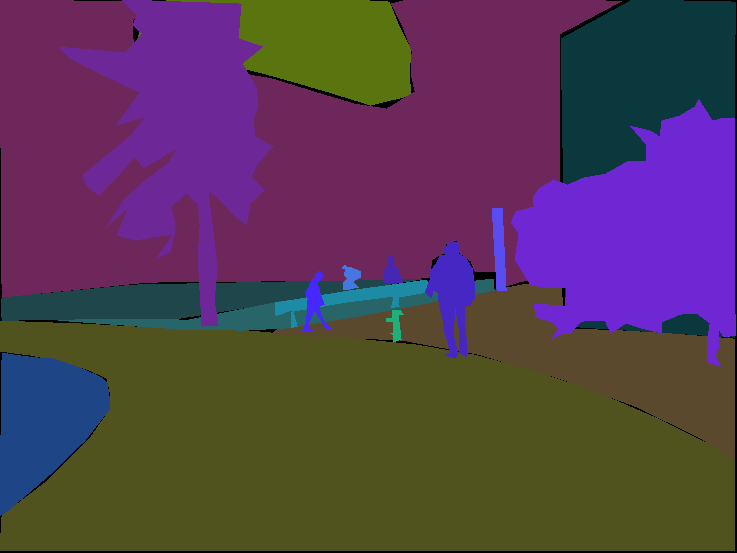

Segmentation is a process of mapping elements in an image. It looks like the following image – each element in the image is assigned a number that represents it – 1 for a person, 2 for a tree, and so on. The computer can be trained to identify what each element in the image is – a tree, a building, a road, or a person – and in our context, what part of the MRI image is the DBS target for Parkinson’s. After training, the computer will be able to recognize, in a fraction of a second, which element is which in the image.

Especially during the COVID period, when everyone was at home, the significant product transformation was completed. To simplify as much as possible – since the problem SIS is trying to solve is a segmentation issue, identifying what in the brain's MRI image is the target for Parkinson’s in DBS surgeries, we minimized the use of registration and switched to using Deep Learning models designed for segmentation problems. Simply put, we taught the computer to identify DBS targets for Parkinson’s surgery.

The advantages are enormous – the product became much simpler, we discarded a lot of old code (which was a great joy), we reduced the runtime from hours to just a few minutes, and we improved the system's accuracy (because every registration has errors, so multiple registrations = multiple errors). Along the way, we were able to add the second DBS target for Parkinson’s, because a model that can map one target in the image will likely, with the right data, be able to map another target as well.

Summary So Far and Insights

In early April 2021, the transformation was completed when SIS received FDA approval for our new algorithm, which can predict with exceptional accuracy the location of all Parkinson's targets and analyze the surgical results based on the post-surgery CT scan. This is not the first FDA approval for me or the company, but it is different. This is the first time I can confidently say that I know the product works the way I wanted it to once I understood what I was supposed to do here. Throughout the project, there were many moments when I didn't know the way, but I always knew where I was supposed to end up. When the team is right and the goal is clear, the path will be found.

Additionally, it was precisely the challenging moments – when the team left, and the uncertainty was so great – that presented the biggest opportunity to shift the technical balance of power within the company to what I thought was the right one.

Danny